This three-part series focuses on the security of, and strategic competition around, fiber optic communications infrastructure – the data super-highways of our world.

Part 1: Optical Core Infrastructure: The Hidden Highways of Connectivity

Part 2: Competing Visions for the Future of the Internet: China’s Strategy to Control the World’s Data Super-Highways

As outlined in the first part of this series, the optical core serves as the backbone of the internet and underpins virtually all global economic activity. A democratic vision of internet governance revolves around advancing the free flow of information, protecting human rights, promoting trust and privacy, and keeping the Internet running for the benefit of all. The US and 70 other international partners affirmed these values in the 2022 Declaration for the Future of the Internet. However, this vision for the internet is being challenged by authoritarian regimes like China and Russia who are seeking to shape the global digital order to meet their strategic objectives, both foreign and domestic. Their evolving alternative model of internet governance emphasizes controlled internet access, data localization mandates, censorship, and repression of the freedom of speech and expression.

Often referred to as the ‘balkanization’ of the web, these competing visions of internet governance are redefining the ways we connect through major infrastructure projects and policy developments around the world. Most recently, the malign influence of both China and Russia on the ongoing United Nations Cybercrime Treaty negotiations has led to draft text which has been criticized by civil society and human rights organizations for criminalizing cybersecurity research, ignoring human rights, and undermining data privacy on a global level. The treaty was meant to be finalized in February 2024 but member states were unable to reach an agreement on a number of issues, pushing the treaty process into limbo.

The authoritarian model of internet governance extends to companies that are subject to the legal jurisdiction of these countries. In China, companies must for instance comply with the 2017 Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China, which features strict localization requirements for certain data as well as expansive government inspection and investigatory powers. They must also comply with the 2017 National Intelligence Law, Article 7, which gives the Chinese government access to any data by requiring that “any organization or citizen shall support, assist and cooperate with the state intelligence work in accordance with the Law, and keep the secrets of the national intelligence work from becoming known to the public.” Finally they must comply with the 2021 Regulations on the Management of Network Product Security Vulnerabilities, which imposes stringent software vulnerability reporting requirements - potentially before a patch is available - a move many have seen as potentially enabling the stockpiling of vulnerabilities for offensive exploits.

Taken together, these pieces of legislation undermine the ability of Chinese network infrastructure vendors to ensure the resilience of their equipment against cyber-attacks and the confidentiality of information that flows through their equipment, even where they have no malign intent. Navigating these requirements can undermine the national security and sovereignty of other countries, no matter the distance in between them.

When it comes to optical core network infrastructure, market dominance by untrusted vendors not only creates security risks, it also serves as a mechanism through which authoritarian regimes can assert their influence and vision of internet governance over global communications infrastructure.

Doing More on the Optical Core Network

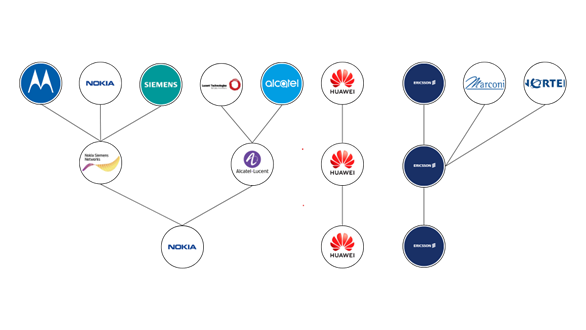

The advent of 5G communications galvanized the US government and several of its allies around the security of the outer edges of our telecommunications networks. Beginning in 2019, as 5G network deployments began, the consolidated nature of the telecommunications market (see diagram below) made the associated risks with untrusted and risky vendors a critical national security risk for democratic nations. As a result, the US, Australia, Canada, India, Japan, New Zealand, Taiwan, and over 10 EU member states have banned new equipment from Huawei and ZTE in their respective countries. These efforts have since slowly expanded to safeguarding more telecommunications infrastructure than just the Radio Access Network (RAN), including recent commitments around securing subsea cables by the G7 in 2024, and by the Quad Partnership in 2023, as well as the recent State Department resourcing commitment for internet connectivity in several Pacific Island Countries.

This focus beyond just 5G hardware is needed, particularly for the producers of optical communications network technology. Given the very real security threats and risks to the optical core network outlined in the first part of this series, as well as the aforementioned alternative vision of digital governance, democratic nations must focus on restricting high risk vendors from developing, maintaining, and ultimately controlling optical core network infrastructure.

Anti-Market Factors

China is the leading exporter of communications technology around the world, with state-backed companies like Huawei and ZTE benefitting from robust financial assistance from the Chinese government in the form of subsidies, grants, credit facilities, and tax breaks. In a global Radio Access Network (RAN) market led by three major vendors, European firms Ericsson and Nokia have struggled to compete with subsidized and inevitably cheaper Huawei bids to provide equipment to network operators. These material price differences are most acute in emerging markets where rapid digitization is driving demand for bandwidth. These markets, spanning much of South-East Asia, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and the Pacific Islands, are a focus of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which uses subsidies, diplomacy, and other state tools to promote Chinese infrastructure projects more globally.

Understanding that outright bans may not be forthcoming in all countries, those committed to an open, free, and secure internet must do more to level the economic playing field, or risk further ceding highways of global connectivity to authoritarian regimes. On quality, reliability, and long-term viability, infrastructure providers from the US, EU, and Japan continue to match or outperform their authoritarian counterparts. This has proven not to be enough, however, against a Chinese industrial complex that is determined to win market share at any cost through the use of non-market-based subsidies.

A Cautionary Tale from the RAN

Telecommunications is a capital-intensive business, with a price-sensitive marketplace. From the 1990s onwards, the likes of Huawei and ZTE worked to dramatically improve their product quality and expand sales across much of the world, especially the global south. These efforts were backed by immense state subsidies and financing from the Chinese government. Between 1997 to 2019, Chinese banks lent Huawei over $14 billion in financing for 99 projects around the world. The lower prices achieved by Chinese vendors through these subsidies, coupled with inaction by the US and its allies, led to a vastly diminished number of Western companies competing in the global telecommunications network infrastructure market, particularly in emerging economies.

As outlined in the 2015 roadmap for the Made in China 2025 strategy, Chinese ambitions in the telecommunications space remain zealous, with goals to acquire upwards of 40% of the international mobile communications equipment market by 2025. Yet their goals around optical communications equipment are even bigger than those for the RAN, with projections for the international market share of Chinese-made optical communication equipment expected to reach a staggering 60% by 2025. This increasing market dominance is mutually benefited by immense academic output. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) found that China is the leading country in advanced optical communications research, with 37.7% of the field’s research produced by Chinese academics versus a mere 12.8% in the US, the next closest nation.

Meanwhile, subsidized overproduction by China in key technology areas from telecoms to electric vehicles poses significant concerns for the viability of these industries in other countries. The concerns are not merely about economic harm, such as reduced profits or fewer jobs. Rather, the concern is existential, insofar as to whether these industries can survive in liberal democracies that do not offer such subsidies.

Without intentional and comprehensive policy making, Chinese vendors will proceed to take the dominant position in the global optical core infrastructure. Once taken, this position will be difficult to reverse. In the third and final part of our series, we will discuss what can be done by governments to protect our core infrastructure from untrusted vendors and secure our internet backbone.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect either way the views of Venable LLP.

Authors

Senior Director, Global Security and Technology Strategy, Venable LLP

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Optical Core Infrastructure: The Hidden Highway of Connectivity