Guzman Berry Field Trip

The source of most Mexican fruit and vegetable exports until 2010 was Sinaloa and the Bajio, mostly the states of Querétaro, Guanajuato and Northern Michoacán. However, in the past decade, Jalisco has become an important producer and exporter, especially of avocados and berries.

The Ciudad Guzman area 135km south of Guadalajara has over half of Jalisco’s berries, the Tapalpa area west of Cd Guzman has a sixth that also has strawberries, and the Jocotepec area west of Lake Chapala a third. A major theme in all three areas is too few local workers to harvest blackberries, blueberries, and raspberries that are produced for export to the US, which prompts growers to recruit workers in poorer states such as Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero; Chiapas is the origin of 70 percent of the migrant workers.

Berries are a high-value and high-risk crop that require significant investments for uncertain returns; high grower returns in recent years have encouraged the berry industry to expand. We found no costs and returns studies such as those available for US-produced berries at https://coststudies.ucdavis.edu/ but were told that the cost of production is generally $8 to $9 per flat or tray for blackberries and raspberries, 12-6 oz clamshells or 4.5 pounds. USDA reported FOB prices for raspberries in April 2018 of $22 a tray, and of blackberries $16 a tray, suggesting significant net returns. The cost of harvesting is less than $1 a tray with payroll taxes, or 10 to 15 percent of grower costs.

The Guzman berry industry is relatively new, but the plastic tunnels covering the plants are a visible reminder of the expanding production. Most tunnels are about 15 feet high and protect five-to-seven rows of berries from the sun, birds, and other elements. Berry farms are fenced, all have security to check entries and exits, and most transport workers between their housing and the fields in buses, meaning no worker cars on site. Toilets and hand washing facilities are readily available.

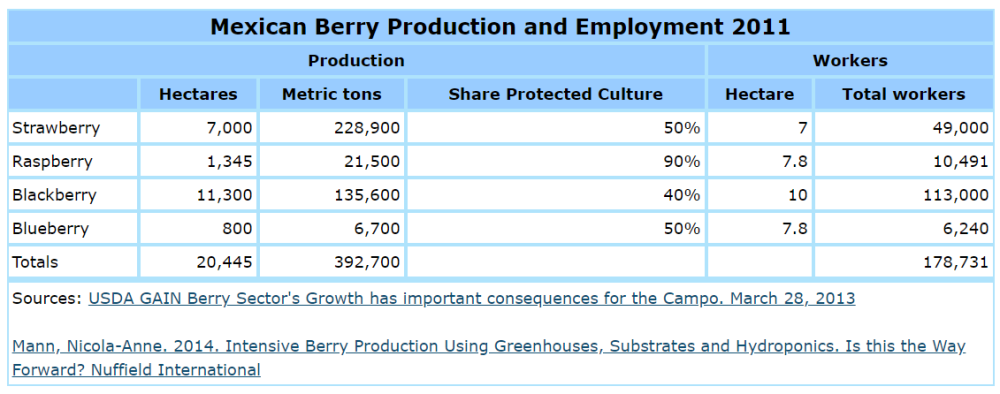

We found no data on average labor requirements or the share of berry acreage grown under plastic tunnels. The production estimates below are for all of Mexico, and they suggest that almost two-thirds of berry workers were employed in blackberries in 2011.

USDA

The berry exporters association reported that the acreage of all four types of berries rose 40 percent between 2011 and 2015 to 28,300 hectares, with the fastest increases for raspberries and blueberries. Aneberries reported that 60 percent of Mexico’s strawberries were in Michoacán in 2015, three-fourths of the raspberries were in Jalisco, 95 percent of the blackberries were in Michoacán, and almost half of the blueberries were in Jalisco.

Workers pick raspberries every day and blackberries twice a week. Most workers pick blackberries and raspberries directly into retail clamshells that are taken to a packing area to be checked and often repacked.

Some growers pick raspberries into two kg buckets. Workers tie six or seven buckets around their around their waists and carry full buckets to a packing area; two buckets fill 12-6 oz clamshells or a 4.5 pound tray. We were told that it is easiest to find workers to pick blueberries, and hardest to find strawberry pickers due to constant stooping, even though piece rate earnings can be highest in strawberries. Tapalpa, which has most of Jalisco’s strawberries, is at a higher elevation and is colder.

The prevailing wage for farm workers in the Guzman area is 150 to 200 pesos per day, at least twice Mexico’s 88 peso a day minimum wage. Most Guzman-area berry growers use piece-rate systems that offer higher rates for greater productivity. For example, blackberry pickers may receive 10 pesos a tray if they pick up to 20 trays a day, 11 pesos a tray if they pick 21 to 25 trays, 12 pesos a tray for 26 to 30, 13 for 31 to 35, and 14 pesos for picking 36 to 40 trays a day. Higher piece rates for faster pickers mean that fewer workers are needed to get the crop harvested and keep the best workers at a particular farm.

Most workers can pick 35 trays of blackberries and 25 trays of raspberries a day, so that 35 trays of blackberries at 13 pesos a tray means 455 pesos ($25) in daily earnings. A typical weekly wage during the peak of the harvest season was reported to be 2,500 pesos ($140) for a six-day, 48-hour week which. We did not see payroll records.

In addition to wages, employers incur payroll taxes of 23 percent for IMSS (workers contribute another 2 percent), five percent for Infonavit, the National Workers' Housing Fund Institute, and workers pay ISR or income taxes that begin at one percent of earnings. A July 29, 2016 Presidential decree exempts employers who pay less than 1.9 times the minimum wage, less than 168 pesos a day, from some payroll taxes in an effort to persuade them to register their workers. We were told that almost all workers employed in export-oriented berries were paid more than 1.9 minimum wages.

Payroll taxes are frustrating for growers because migrants find it hard to access IMSS services both where they work away from home and in their home areas, where IMSS often has no facilities to provide health care. Some growers provide medical services to all their workers at their expense but, instead of receiving credit from IMSS for the services they provide, IMSS wants to continue to collect taxes on all wages paid to farm workers and experiment with mobile clinics and other mechanisms to provide services to farm workers, as IMSS has been doing around Jacona, Michoacán for workers employed in strawberries. Some Guzman-area workers were able to obtain preventive health care services under the IMSS PREVENIMSS programs, which encourages them to make return visits for check ups.

Infonavit is a government agency that collects payroll taxes to help workers to buy homes. Infonavit mostly provides housing subsidies for year-round workers in major cities, but is experimenting with subsidizing housing in smaller communities. Employers must contribute on behalf of workers for 16 consecutive months to be eligible for Infonavit subsidies, and few seasonal farm workers accumulate enough Infonavit credits to obtain subsidies and build houses, less than five percent at one major grower over two decades, prompting growers who pay Infonavit taxes and provide housing to say that they pay twice, for the housing they provide at no cost to migrants and for Infonavit subsidies that few of their workers receive.

Infonavit owns many abandoned housing units. The Los Angeles Times reported November 26, 2017 that, between 2008 and 2013, Infonavit supported the construction of a million mini-casas, one bedroom units with 325 square feet, smaller than a typical two-car US garage, that were sold to those who accumulated enough credits for $20,000 to $30,000. Many Infonavit housing developments were built in flood zones and some developers did not complete water or sewer services; local governments often refused to complete what developers should have done. Homex and major builders Casas Geo and Urbi filed for bankruptcy protection in 2014.

The peak berry harvest season in the Guzman area is March-April-May. As yields drop, a major challenge is to retain migrant workers when there are other high-earning crops available to pick in other regions. Migrants with land at home often want to return to their farms, prompting some berry growers to offer end-of-season bonuses, paying one or two pesos for all trays picked during the entire season to retain workers. These bonuses reportedly persuade 90 percent of pickers to stay until the end of the season.

Many growers employ a mix of local and migrant workers, although migrants and local workers are often segregated in the workplace and in lunch and rest areas. A berry farm with 40 hectares or 100 acres of blackberries and raspberries had 240 workers, and provided housing for the migrants who were about half of the total workforce.

Migrants are often preferred workers. They tend to be faster pickers and are willing to work longer hours and Sundays if needed, while local workers may not show up every day and may refuse extra hours. Employers believe that migrants value extra wages more than extra benefits. Migrants are about 80 percent men and 20 percent women, while the sex ratio local workers varies with the season. During non-harvest periods, local men outnumber women, but during the harvest season, local women outnumber men, as in blackberries, when women may be three-fourths of local harvesters.

Network hiring is prominent, with current workers bringing or recommending friends and relatives and often taking responsibility to train and orient them at work. Recruitment, transportation, and pay advance systems vary, and some recruitment practices reflect conditions in worker areas of origin.

Some communal villages in Chiapas require workers to leave to pay exit taxes of 200 pesos ($12) because, by leaving the village, they are not available to perform the community service work required of residents; those who do not pay risk loss of their homes and ostracism. Workers in these cash-poor areas often need to borrow money to pay exit taxes and transportation, which can involve 2-3 days bus trips to export-oriented farms. Some growers send a bus to pick up migrants and have the driver provide them with food en route to Guzman at a cost of 2,000 pesos per worker, equivalent to a week’s wages.

There is no doubt that some migrants arrive in Guzman with debts. These debts may be to their local communities or represent pay advances to sustain their families until they earn and remit. Some growers deduct pay advances and transportation costs from workers wages, while others do not.

One grower built a labor camp for 600 migrant workers who have five-month contracts. The migrants, 80 percent men, are housed four workers per room, with each worker entitled to 4.6 square meters. Employer housing costs are 28 pesos ($1.55) per worker per day or $46 per month, but it was not clear if this represents only operating costs or includes construction costs. The employer pays for kitchen staff at the camp who cook and serve food.

The camp provides transportation to and from fields that are up to 1-2 hours away. Workers normally work from 7am-3pm with lunch from 10:30-11am. Workers pay 70 pesos or $4 a day for meals that are provided in an on-site cafeteria. The camp has a training room that offers after-work classes in literacy and other topics; alcohol is banned. As in Salinas, some local workers in Guzman asked growers for the same free housing that was provided to migrants.

These observations lead to three major conclusions:

- Expansion and Migrants. The Guzman area has the climate, land, water and infrastructure to produce more high-quality berries for export. Local farmers and investors have access to capital to begin or expand berry operations and take advantage of a very profitable crop, but there is not enough local labor to harvest the berries. Growers recognize that a major threat to berry farming is the availability and treatment of migrant workers, and they are cooperating and paying for efforts by major berry marketers to establish and promote best practices to recruit, house, and supervise migrant workers.

Labor appears to be the most scarce resource for the berry industry. Most growers register their workers with government agencies and pay required taxes, unwilling to risk the government fines and loss of access to the US market. There were reports of crew leaders circulating to other farms’ housing and trying to recruit workers to move to another grower. Despite five or eight-month contracts, we were told there are no penalties for workers who break contracts and change employers.

- Reactions. There is local opposition to the expanding berry industry that appears motivated more by environmental than labor issues. For example, the level of the local lake is rising due to silt, which prompts worries about the lake’s capacity to store water.

Several opinion leaders asserted that the chemicals in the plastic pipes used to irrigate berries are raising cancer rates for residents, but none complained of berry workers settling with their families and imposing education, health care, and other costs on Guzman. One reason for limited settlement is that most migrants are solo men and women; if berry harvesting were to expand from five to eight months, there may be more settlement.

When migrants settle with their often large families, they can experience discrimination at the hands of local residents and governments. This reportedly occurred in the San Quintin area of Baja, where the local government did not provide services to farm workers who settled in homes away from the farms where they worked; some local schools reportedly refused to enroll migrant children.

The Guzman area has an active logging sector; trucks bring logs to area mills. Berry and other farming activities generate dust, which many farmers try to reduce by sprinkling water on farm lanes. The berry industry is supporting reforestation by planting rows of trees to reduce wind damage to the fruit; the industry also supports reforestation in the area.

- H-2A. Some migrants in the Guzman area have done farm work in the US, but are in the Guzman area because they were apprehended or decided to return on their own. The US AEWR of $13.18 an hour in California for H-2A workers is very attractive to berry pickers who earn $2 to $3 an hour in Guzman. Some growers with partners or operations in the US are offering to take their best Guzman-area pickers to California for the summer-harvesting season. US berries are the largest users of H-2A workers, and half of the workers in the Salinas-Watsonville area are believed to be H-2A workers.

We did not learn about smaller berry growers or avocado labor. The largest 10-20 Guzman berry growers likely produce 70-80 percent of the area’s berries, but we were told of smaller growers who may be sharecroppers. Marketers provide them with land, plants, and advice, and share the proceeds from the sale of the crop 50-50 with the farmer. We did not visit any sharecroppers, who may hire some workers in addition to family members.

Avocados, like oranges in Florida, are often sold on the tree to buyers who harvest them. In the Guzman area, avocados are harvested during the summer months by crews of workers from Michoacán who are certified for food-safety and other considerations. Unlike Michoacán, Jalisco avocados may not be exported fresh to the US, but Jalisco growers anticipate being certified to ship fresh avocados to the US. The avocado industry is expanding rapidly in Jalisco, often with capital from nonfarmers who see opportunities to earn high returns. There were whispers of drug money being recycled via avocado production.

About the Authors

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more