H-2A: Recruitment and Adverse Effect Wage Rates (AEWRs)

Through the United States' H2-A program, farmers who anticipate labor shortages can recruit and employ foreign works to fill seasonal jobs. There are more workers who want H-2A visas than there are H-2A jobs, so some workers pay recruiters for jobs. In this article, Philip Martin describes the recruitment process for H2-A workers, describes challenges they may face in obtaining fair wages, and presents survey data on North American farm workers.

BearFotos, Shutterstock

This publication is part of the Wilson Center Mexico Institute's initiative on Farm Labor and Mexico's Export Produce Industry, made possible by generous grants from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation and the Walmart Foundation.

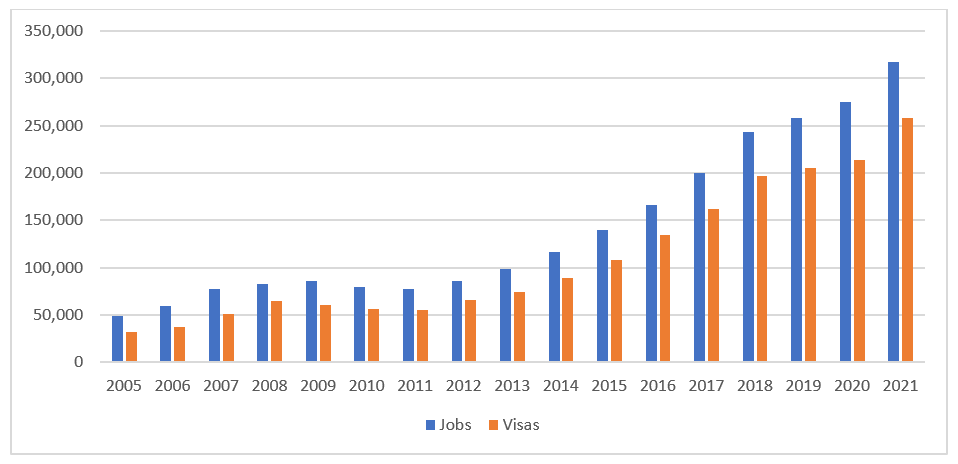

The H-2A program allows farmers who anticipate labor shortages to be certified by Department of Labor (DOL) to recruit and employ H-2A workers to fill seasonal jobs that last up to 10 months. There is no cap on the number of H-2A workers, and about 10,000 US farm employers were certified to fill 317,000 seasonal farm jobs with H-2As in FY21.

The number of jobs certified has been increasing, tripling over the past decade. About 80 percent of H-2A jobs certified result in the issuance of H-2A visas; some 258,000 H-2A visas were issued to foreigners in FY21. Over 99 percent of H-2A visas went to citizens of four countries: Mexico, 93 percent, South Africa, three percent, Jamaica, two percent, and Guatemala, one percent.

The number of H-2A jobs certified tripled between FY13 and FY21 to 317,000

Philip Martin

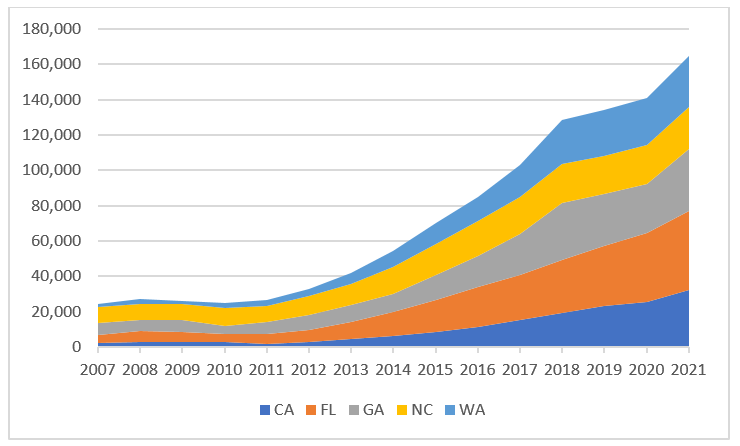

Over half of H-2A jobs are in five states: California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Washington. The share of H-2A jobs in these five states rose from 34 percent in 2007 to 52 percent in 2021 due to the growth in each state and especially in California and Washington.

The top 5 states had 52% of H-2A jobs in FY21; CA and WA H-2A rose fastest

Philip Martin

Recruitment. H-2A regulations require employers to pay all worker expenses, including the cost of the H-2A visa and the cost of travel from US consulates to and from US workplaces. Regulations prohibit US employers or their agents in migrant-sending countries from charging workers for US jobs that may pay 10 to 20 times more than the workers could earn at home.

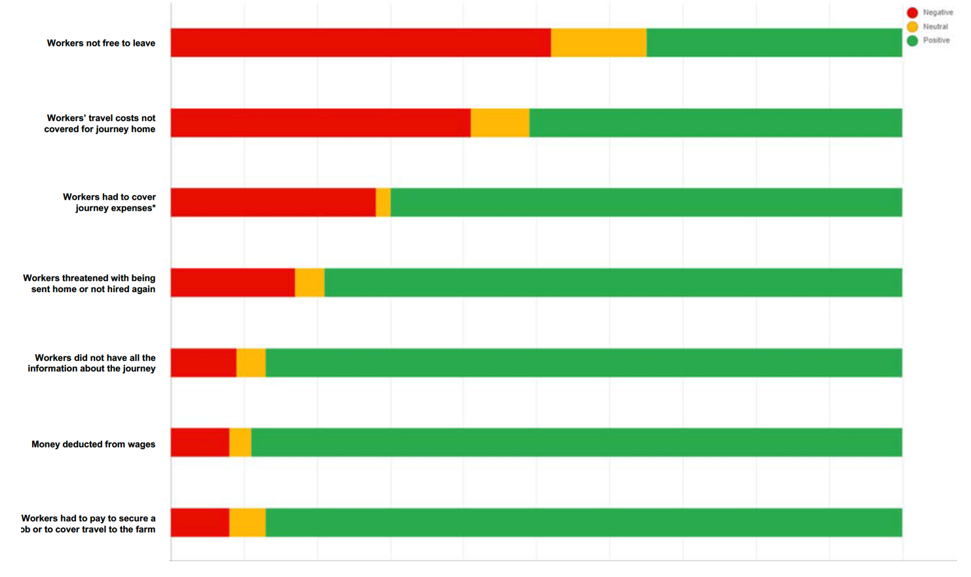

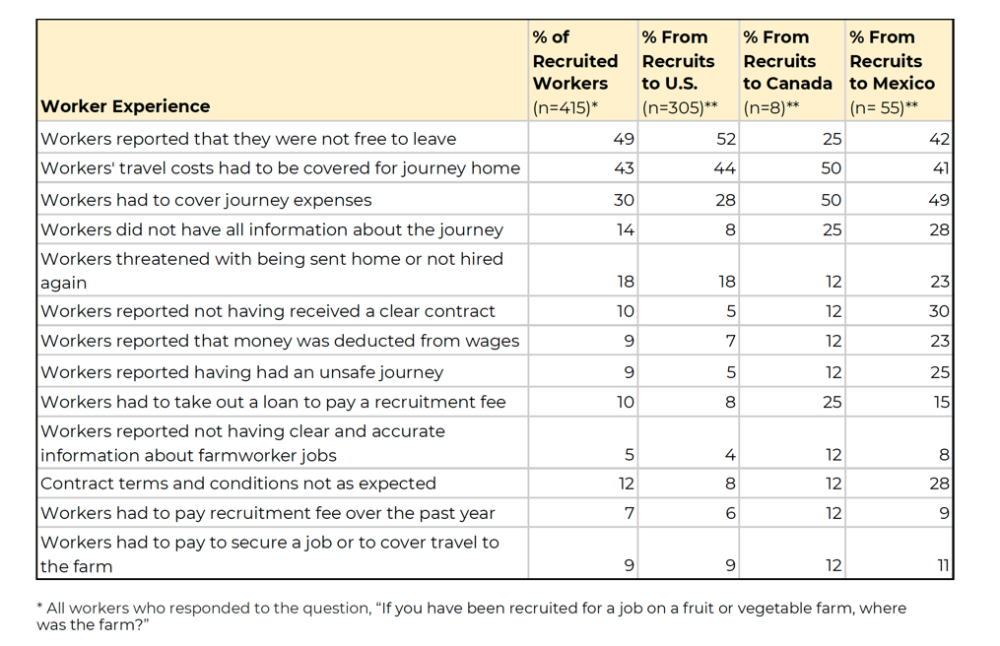

There are more workers who want H-2A visas than there are H-2A jobs, so some workers pay recruiters for jobs. A survey of over 400 workers in Mexico conducted via mobile phones over eight months in 2020-21 found that many felt unable to leave their farm jobs, had to pay their own travel costs to return home, or had to cover some of their expenses while traveling to their farm jobs. Migrants wanted freedom from threats at workplaces away from home and guarantees of no unexpected expenses.

The survey asked: “Did you feel like you had the option to leave the job if you felt unsafe or if the terms and conditions of your contract were not being met?” Feeling unsafe was not further defined, and terms and conditions of contracts can vary between what workers are told orally and what is in their written contracts. Guest workers who lose their jobs can lose their right to remain legally in a foreign country, which could be interpreted as being unable to leave a job and staying abroad legally.

Very few workers paid for their jobs or had deductions from their wages

Philip Martin

Few workers were threatened with being sent home or not being rehired. Almost all workers had full information before arriving abroad, few had unexpected deductions from their wages, and few paid for their jobs. Almost three-fourths of the workers went to the US, followed by 13 percent who were internal migrants recruited to work away from their homes within Mexico. Some survey respondents were not recruited to work on fruit and vegetable farms.

Mexican workers were asked a series of questions about the jobs they sought or for which they were recruited. Over half of the workers who were recruited to work in the US said they were not free to leave their US workplaces, as did over 40 percent of the migrants recruited to work on farms in Mexico. Over 40 percent of the workers who were recruited to work on US and Mexican farms reported that they paid for their journey home.

Many migrants said they were not free to leave their workplace, but few paid recruitment fees

Philip Martin

The share of migrants who complained of not receiving a clear contract or having deductions from their wages was higher for those recruited to work on Mexican than on US farms. Only eight workers were recruited for Canadian farms, and they reported more problems than workers who were recruited for US farms.

Some of the survey questions could generate ambiguous responses. For example, workers can only report being afraid to leave their jobs abroad or paying for return transportation after they have returned. However, some of the questions referred to workers “heading to” US or Canadian farm jobs, suggesting that worker responses dealt with anticipated experiences or experiences in prior years.

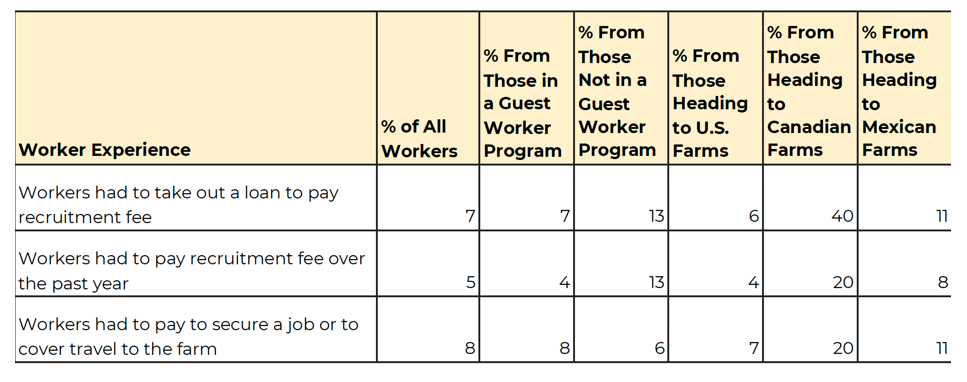

Workers headed to Canadian farms were most likely to report paying recruitment fees

Philip Martin

Among 400 respondents to the question, “how much do you expect to pay in recruitment fees to get a job on a farm,” 80 percent reported nothing and 14 percent reported less than $3,000. However, interviewers reported that some workers, when asked how they would make recruitment “less expensive for people like you” said that they paid for their farm jobs.

Interviewers asked workers whether they thought employers often threatened workers to get them to work faster or to work more hours by saying they would not be rehired next season, and 70 percent said yes. When asked if employers promise to rehire workers who volunteer to work extra hours next season, half of the workers said yes.

The recruitment study concluded that migrants want reliable information, a peer community, and protections from threats and unexpected fees when away from home. Many survey participants were recruited by CIERTO, an NGO that works with local community groups and does not charge fees to the H-2A workers it recruits.

AEWRs. DOL issued proposed regulations December 1, 2021 that would replace the current system of one AEWR for all H-2A workers in a state with several AEWRs per state that reflect the type of job being filled. The purpose of the change is to deal with mis-classification, as when employers call truck drivers or construction workers farm workers in order to pay them the lower AEWR wages derived from crop and livestock workers.

The current AEWR is the average hourly earnings of crop and livestock workers who were hired directly by farmers during the previous year, so that CA’s $17.51 AEWR for 2022 reflects the average hourly earnings of the state’s crop and livestock workers in 2021. USDA surveys 18,000 US farms in July and October, and half report employment and earnings data for the week that includes the 12th of January, April, July, and October. USDA divides earnings by hours worked to obtain average hourly earnings for 15 multistate regions and California, Florida and Hawaii.

Since 2014, USDA has ask farm operators to report hired workers, hours worked, and earnings by Standard Occupational Classification (SOCs) codes, such as farm workers, crop, nursery, and greenhouse (42-2092) or farm workers, farm, ranch, and aquacultural animals (42-2093).

The October 2021 FLS survey reported 772,000 workers employed directly by US farmers, including 373,000 crop workers, 150,000 animal workers, and 136,000 ag equipment operators. Under DOL’s proposal, 90 percent of H-2A jobs would be in the six SOCs that would continue to have one AEWR per state based on the earnings of crop and livestock workers.

DOL proposed that AEWRs for the remaining 10 percent of H-2A jobs, including farmers and supervisors and drivers and construction laborers, be the average wages determined by the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics survey. In 2020, when the average US AEWR was $14 an hour, the average US OEWS wage for heavy truck drivers (SOC 53-3032) was over $23 and for construction laborers (47-2061) almost $21. DOL proposed that workers with several different jobs, such as harvesting and driving, should be paid the highest AEWR for all their hours worked.

DOL normally accepts employer job descriptions. Farm employers who now employ drivers and construction laborers as crop workers would have an incentive to mis-classify their jobs as crop workers in order to pay lower wages.

Perspective. Labor costs are 10 percent of farm production costs, but higher in nurseries and greenhouses, 33 percent, fruit and tree nuts, 30 percent, and vegetables and melons, 22 percent. The average hourly earnings of farm workers have been rising faster than those of nonfarm workers, making the average $15 an hour farm wage in 2021 about 60 percent of the average $25 an hour for nonfarm workers.

Setting AEWRs by job title requires employers to specify the tasks that their H-2A workers will perform and offering and paying the appropriate wage. DOL agencies and state workforce agencies will have to determine if employer-specified job titles are accurate. Some farm employers worry that their labor costs will rise because workers who have several job titles could have AEWRs set by the OEWS.

About the Author

Philip Martin

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more