Introduction

The past few years have seen intensifying Global South discontent intersecting with rising major power competition in the world and the Indo-Pacific region in particular. Key developing countries are seeking to carve out an independent path. China and Russia are shaping the agenda to blunt US power. Washington and its allies are trying to respond to a contested, shifting landscape. The intersection between Global South contestation and strategic competition is critical to the world’s trajectory and US interests. The emerging balance of power will shape the contours of competition and cooperation across geopolitical and geoeconomic domains as well as the world’s most serious shared challenges for decades to come. The stakes are particularly great in the Indo-Pacific, the primary theater of major power competition that encompasses around two-thirds of the world economy, more than half its people and seven of its largest militaries.

This policy brief explores the intersection between Global South contestation and strategic competition and the opportunities and challenges therein. It is informed by conversations with policymakers and experts across key Global South capitals and trips to Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Pacific over the past few years. The brief makes three arguments. First, there are five important common objectives embedded in Global South contestation despite divergences and definitional issues. Second, Global South contestation is already showing signs of intersecting with strategic competition across four key domains: the diplomatic, informational, military and economic realms. Third, actors, including regional states as well as the US and its partners, can help shape evolving dynamics within this intersection and better manage North-South divides.

Global South Discontent in Perspective

The Global South is a shorthand to describe a diverse grouping of over 130 primarily postcolonial developing countries largely in the Southern hemisphere spanning Africa, Asia and Latin America. Many of these Global South countries fought against colonialism and were part of groupings during the Cold War like the Group of 77, which now comprises 134 countries or about 80 percent of the world’s population. Today, despite the term’s limitations, it has grown in popularity relative to outdated alternatives like “Third World” used in the 1970s and 1980s to describe development disparities. The rising attention to the term comes amid a confluence of developments that have intensified Global South discontent. These include the shrinking space for agency amid polarizing major power competition and frustrations with slow pace of institutional reform. UN and EU officials have acknowledged usage of the term, and it has appeared in US strategy documents despite recognition of its limitations.

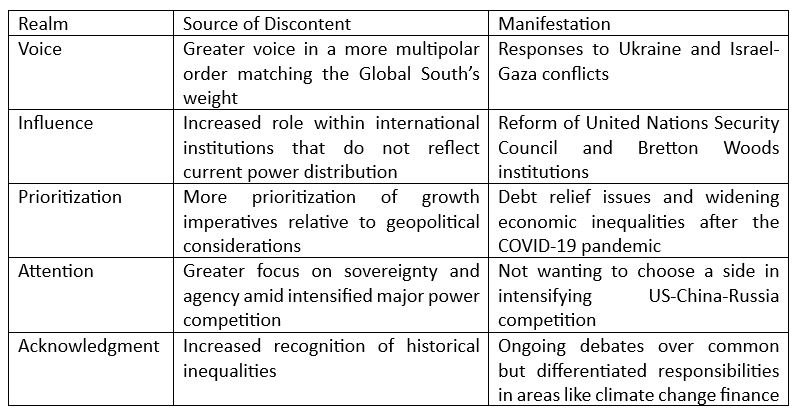

Despite divergences, the alignment of Global South discontent is largely around the need for a more just and equitable geopolitical and geoeconomic order that reflects the rise of the rest relative to past Western domination. One Global South official described this as “vectors of discontent” that have some similarities even if that do not amount to specific interests. India’s foreign minister S. Jaishankar has said Global South also captures a more intuitive mindset rooted in principles like looser alignments and shared solidarity that are non-Western but not anti-Western. Careful content analysis of speeches by officials across key Global South countries suggest discontent revolves around five axes (see table below): 1) more voice in a multipolar order; 2) more influence in institutions; 3) more prioritization of growth relative to geopolitics; 4) greater attention to sovereignty and agency; and 5) fuller acknowledgement of historical inequalities.

To be sure, these common threads of discontent are expressed differently. India has advanced its 4R proposal of “respond, recognize, respect and reform” in the global order, while China has emphasized vaguer principles like solidarity in its four point proposal. Countries like Brazil have highlighted inequality amid domestic challenges on this front, while others like South Africa pushed moral conflict activism. Yet practitioners also recognize that addressing sources of this discontent remains critical. Singapore’s ex-top diplomat Bilahari Kausikan, who engaged with groupings like the G77, has noted that failure to take Global South discontent seriously by Western countries can pave the way for inroads by countries like China. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell has linked countering pro-Russia sentiment in the Global South with meeting demands for greater institutional space.

Where Global South Discontent Meets Strategic Competition

The current wave of Global South discontent is converging with intensified major power competition across the world and the Indo-Pacific in particular. China views the Global South as an area to blunt US influence and advance its three global initiatives and recalibrated Belt and Road Initiative. By one count, China could eclipse Washington’s half-century-old position as the most powerful and influential country in the G77 by 2040. One official privately characterized the US challenge as Washington needing to simultaneously cultivate both “Indo-Pacific depth” and global breadth” as it relates to regions of the Global South, which is a different proposition than past notions of a “pivot” to Asia. Yet this is far from a US-China contest. Russia sees the Global South as a way reduce isolation after the Ukraine war. Key nations from Asia, Europe and the Middle East, including Japan, are making inroads in the Global South that US officials acknowledge Washington is learning from. Rivalries within the Global South also remain, whether it be Sino-Indian rivalry or intra-region leadership struggles in Africa or Latin America.

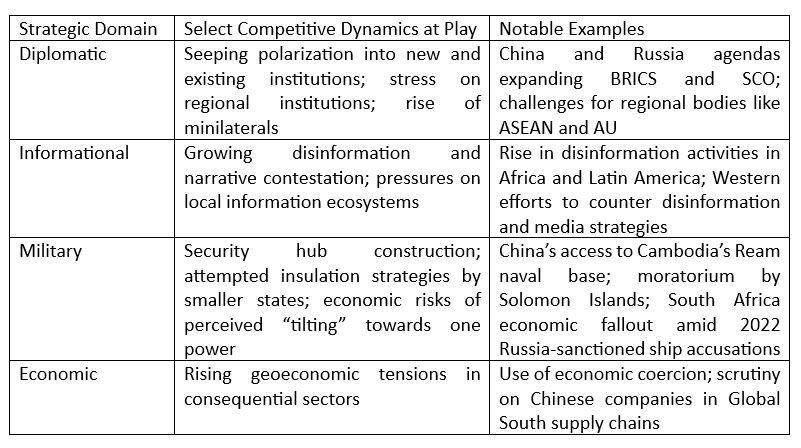

The convergence between the twin realities of Global South discontent and intensified major power competition is increasingly recognized by both countries within it as well as partners with it. Leaders such as Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Papua New Guinea Prime Minister James Marape and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa have noted the tensions between the geopolitical realities of a polarized world and the urgent need to confront pressing development challenges. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres has been blunter in arguing for simultaneously addressing both a “21st century Thucydides trap” in US-China competition and a deepening “North-South divide.” The convergence of these twin realities is already seen across four domains within the so-called DIME framework: diplomatic, informational, military and economic.

The convergence between the twin realities of Global South discontent and intensified major power competition is increasingly recognized by both countries within it as well as partners with it.

First, in the diplomatic domain, as Global South countries try to boost diplomatic space, polarization is seeping into institutional expansion. Beyond positive stories like the African Union’s addition to the Group of Twenty (G-20), China and Russia have leveraged institutional additions of Global South countries to advance their own agenda to blunt US power via the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS grouping. Regional institutions have also come under stress. Examples include severing of ties by junta governments with the Western African grouping ECOWAS and proposals to form new Latin American blocs. Washington and its partners are responding by trying to forge new Global South pacts beyond minilaterals like the Quad or NATO Asia links. One example US officials refer to is the 2023 Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation, which includes countries from Africa, South America and the Caribbean, specifying commitment against coercion.

Second, in the information domain, as Global South countries try to project their own voices, narrative contestation and disinformation increase the risk of information ecosystems being manipulated against country interests. Some data already point to a multifold increase in disinformation activities in parts of the Global South like Africa and Latin America. This is fueled in part by greater anti-Western narrative alignment between China and Russia. These activities extend beyond legitimate major power narrative competition. In response, the US has quietly intensified work with key Asian and European allies to combat Chinese and Russian disinformation and counter certain media strategies such as content-sharing pacts, training programs and censorship. There have also been efforts to grow local and regional media networks under initiatives like the Digital Communication Network.

Third, in the military domain, as Global South countries build capacity to manage security challenges, major powers are intensifying scrutiny around these decisions and their wider impacts. The battle for base-like locations has gotten much of the attention. For instance, Washington has assessed China eying new military facilities in nearly 20 Global South countries across three continents including Cambodia’s Ream naval base. Officials say temporary foreign vessel moratoriums instituted by countries like Sri Lanka and the Solomon Islands highlight pressures of fierce geopolitical competition in spaces such as the Indian Ocean and Pacific Islands involving powers like Australia, China and India. The economic fallout in South Africa after accusations tied to the docking of a sanctioned Russia ship in 2022 spotlighted impacts of the Kremlin’s role as a top arms supplier in Africa following the Ukraine war. Moscow’s presence has also included mercenaries following regime changes.

Fourth, in the economic domain, as Global South countries are trying to grow and bridge development gaps, geoeconomic tensions are rising in key sectors. These tensions pose serious challenges that coexist with opportunities for supply chain diversification beyond China and new opportunities in just energy partnerships and economic corridors emerging out of Western countries. While officials in Global South countries may not publicly voice concerns, the risks of overdependence on China have been evident in instances like Beijing’s role in Indonesia’s critical minerals space or use of economic pressure affecting countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Growing scrutiny on Chinese companies in Global South supply chains also worry governments like Mexico and Vietnam as China shifts economic activity in response to so-called “small yard, high fence” restrictions. The risks of growing global fragmentation are significant: the IMF estimates losses could be as high as 7 percent of global GDP, mostly affecting the Global South.

Policy Implications

Adjusting to the intersection between rising Global South discontent and intensifying major power competition will require actions from a range of actors including institutions, regional states and key powers. For the US and its partners, efforts to adjust to these realities would ideally provide a foundation for countries to address perceived grievances and challenges, respond to changing geopolitical shifts as well as reinforce a free, open and multipolar order.

Helpful Actions by Global South Countries

1. Strengthening regional anchoring.

Regional Global South leaders should strengthen indigenous institutions that help manage intraregional dynamics amid major power competition. Part of this is managing institutional stress in areas like flashpoint stabilization and membership changes, as we have seen in bodies like ASEAN or ECOWAS. It is also critical to push opportunities that accelerate growth. Visions like the Pacific Island Forum’s 2050 Blue Pacific Continent Strategy can link global competition with pressing development priorities. Keeping the momentum up on regional initiatives on cross-border payments or the African Union-led Africa Continental Free Trade Area can also facilitate regional cohesion in an era of global fragmentation.

2. Cultivating swing sector ecosystems.

Individual Global South countries should ensure they are strengthening their own ability to make decisions in key strategic industries or “swing sectors” where major power competition is fiercest, like emerging technologies or critical minerals. This includes setting up domestic ecosystems to weigh alternatives and insulate decisions from capture. More effort should also be placed on socializing these approaches globally and addressing differences with those of advanced economies. One area of focus could be ways to evaluate incoming and outgoing investments that impact key national security areas, even if these fall short of robust investment screening mechanisms. Another could be forging smaller agreements with like-minded partners that extend beyond a single power. One example is the Philippines’ attempt to forge a trilateral critical minerals partnership building off of US-Japan alignment, amid what some view as a challenging environment to secure deals with Washington bilaterally.

“Individual Global South countries should ensure they are advancing their own national interests through choices made in key strategic industries or “swing sectors” where major power competition is fiercest, like emerging technologies or critical minerals.”

3. Leveraging agency to ensure an inclusive Global South agenda and narrative.

Active countries like Brazil, India and South Africa should continue to ensure that the Global South agenda is shaped around a multipolar order, rather than one dominated by any single power including China. This can reinforce Global South agency and cool heated competition from rival powers countering Beijing. There should also be an emphasis on cultivating diverse spokespeople who can help advance a Global South narrative and bridge North-South divides. Beyond figures in government, non-governmental actors can also help advance South-South cooperation, as evidenced by work being done by groups like the Observer Research Foundation in India and the Policy Center for the New South in Morocco.

Helpful Policy Actions by the US and its Allies

4. Flexibly managing institutional tradeoffs and cultivating North-South bridges.

Developed countries should continue to push for more Global South representation to give countries more of a say and blunt efforts by some powers to exploit discontent. Focus should be placed on meaningful efforts like advancing OECD roadmaps for candidates like Argentina and Indonesia to catalyze structural reform not seen in institutions like BRICS. Smaller minilaterals also play a key role. The G-7 should continue to be utilized to seed standard-setting conversations in areas like countering economic coercion, and the Quad can pursue cooperation with individual Global South countries if it addresses issues relevant to them as we saw with COVID-19 vaccine attempts. Periodically convening fora beyond formal institutions can help inject momentum into pressing challenges. A case in point is a 2023 summit on global financing held in Paris, spotlighting the issue of debt distress affecting about 60 percent of the world’s poorest countries.

5. Delivering on selective, high-impact commitments with an affirmative framing.

Advanced economies should focus more on advancing affirmative sectoral agendas rather than countering initiatives by other powers. Focusing on promoting standards and alternatives in strategic industries will better align strategic competition with developing country priorities rather than the aggregate lens of major power contestation. For instance, promoting Open RAN adoption has proven more effective than keeping Chinese firms like Huawei out in the telecommunications space. Where developed countries cannot directly compete such as infrastructure project construction, other pathways should be considered, such as boosting soft infrastructure in areas like evaluation or boosting lending capacity of development banks. Delivering on commitments made will be critical. As one African diplomat pointed out on the sidelines of a conference, there are worries that “Western commitment bombing” designed to create the perception of countering China may not actually be followed through.

6. Localizing partnerships and messaging.

The US and its allies and partners should intensify localizing partnerships and messaging beyond addressing aggregate Global South concerns. Local capacity-building by institutions like the US State Department’s Global Engagement Center with individual Global South countries will be more effective in shaping governance and media networks in countries than perceived US criticism on democracy and human rights. Strengthening links with small businesses and youth groups on areas like digital upskilling can also help ensure that developing countries play a role in consequential domains like artificial intelligence.

Ultimately, it is the diverse people of the Global South that will make meaningful differences in their countries much more so than the efforts of any single outside power. Collectively, these actions by the Global South and the West can help address and manage rising discontent among strategic competition.

Author

CEO and Founder, ASEAN Wonk Global, and Senior Columnist, The Diplomat

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Global Alliances: Tankers and Yachts

US Inaction Is Ceding the Global Nuclear Market to China and Russia