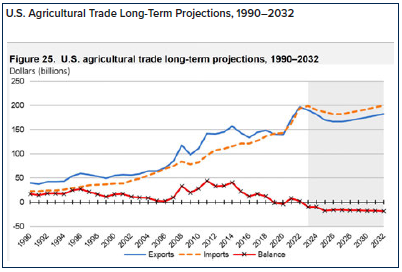

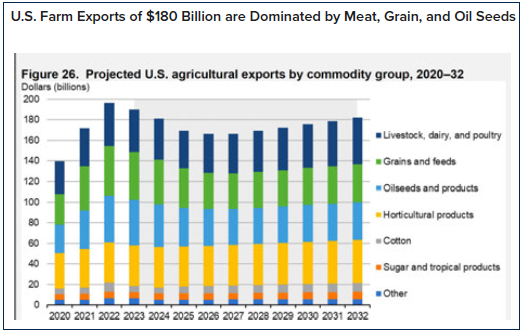

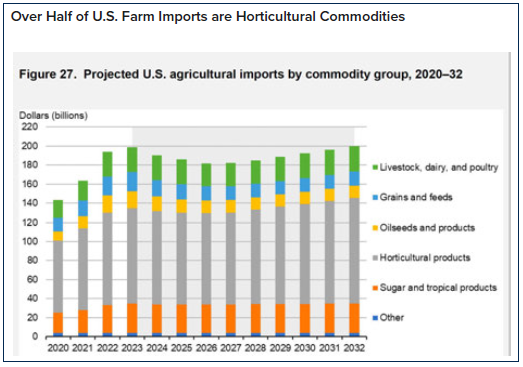

The value of US farm exports exceeded the value of US farm imports between 1990 and 2020. The value of US farm imports is rising faster than the value of US farm exports, leading to farm trade deficits that are projected to widen.

The major reason for the US farm trade deficit is more imports of horticultural commodities, including imports of beer worth $7 billion in 2022, wine worth $7 billion, and spirits worth $12 billion. Alcoholic beverage imports of $26 billion were about the same as the combined value of imported fresh fruit, $18 billion in 2022, and fresh vegetables, $11 billion.

The US exports mostly meat, grains, and oil seeds, and imports primarily horticultural commodities, reflecting US comparative advantage. Soybeans worth $27 billion were the most valuable farm export in 2021, followed by $19 billion worth of corn and $8 billion worth of wheat. Other major farm exports were tree nuts worth $8 billion in 2021 and cotton exports worth $6 billion.

A third of the $100 billion in US horticultural imports are fresh fruits and vegetables, including avocados, berries, and citrus from countries such as Mexico, Chile, and Peru. The $46 billion value of horticultural imports from Mexico in 2022 includes fresh fruits and vegetables and alcoholic beverages.

Fresh Produce

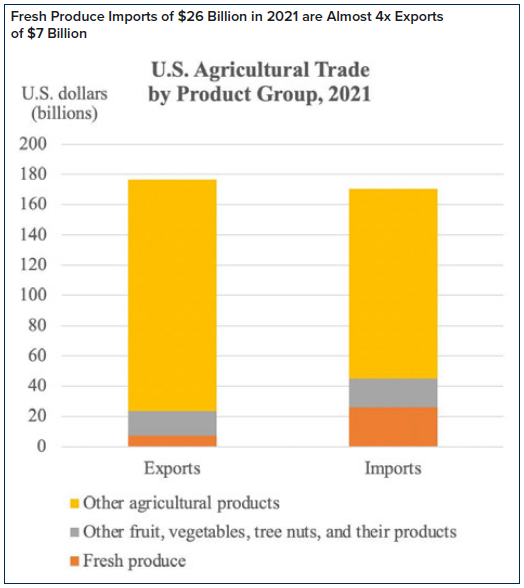

Fresh fruits and vegetables are a relatively small share of US farm exports and a larger share of US farm imports. The value of fresh produce exports, $7 billion, is only four percent of total US farm exports. However, the value of fresh produce imports, $26 billion, is an eight of total US farm imports.

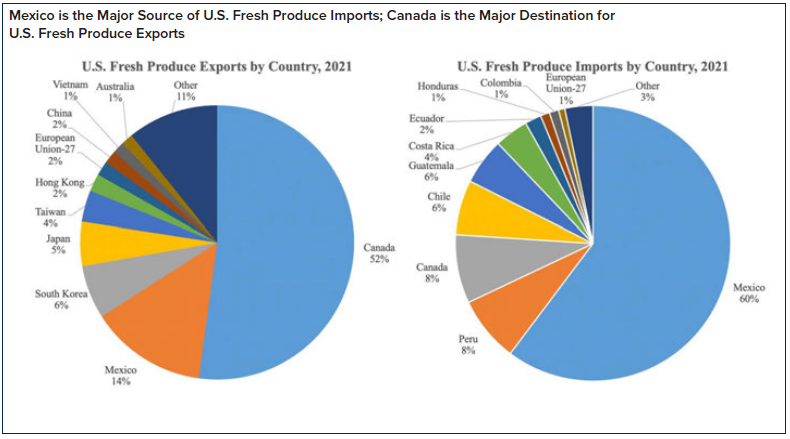

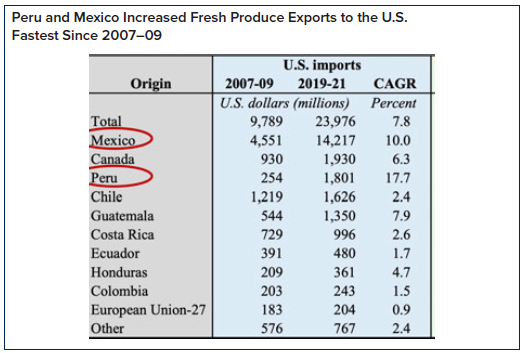

The major destination for US fresh produce exports is Canada, while the major origin of US fresh produce imports is Mexico. Imports of fresh fruit from Peru are rising fast, so that Peru in 2021 surpassed Chile as the major supplier of US fresh fruit imports during the winter months.

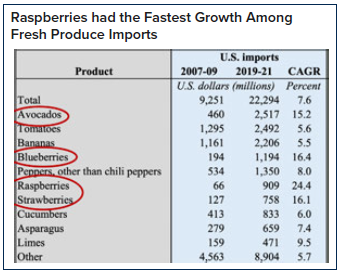

The value of US fresh produce imports has been rising at an eight percent annual rate, and faster for Mexico, up 10 percent, and Peru, up 18 percent.

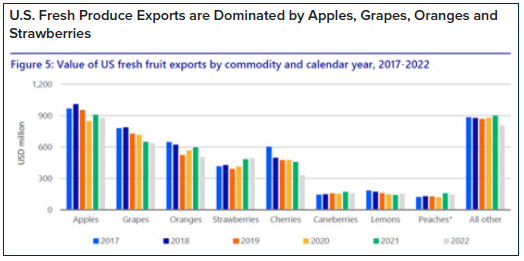

Fresh apples are the most valuable US fresh produce export. Apple exports were $900 million in 2021 or an eighth of US fresh produce exports of $7 billion. The next leading fresh produce exports are grapes worth over $600 million, and oranges and strawberries each worth about $500 million.

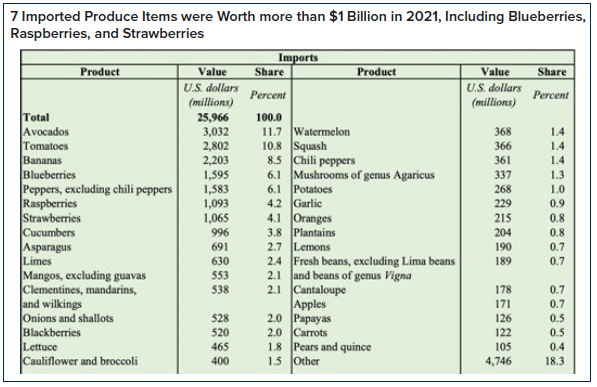

Avocados and tomatoes were the most valuable fresh produce imports, worth almost $6 billion in 2021 or a quarter of the $26 billion of fresh produce imports. Mexico produced almost four million metric tons of tomatoes in 2022, including a quarter in Sinaloa, an eighth in San Luis Potosi, and a tenth in Michoacan. Most Mexican tomatoes are grown in greenhouses, shade houses, and high-tunnel systems, and over half of Mexico’s tomatoes are exported.

Berries had the fastest growth among fresh produce imports, led by raspberries, blueberries, and strawberries. The value of berry imports rose by over 15 percent a year between 2007-09 and 2019-21.

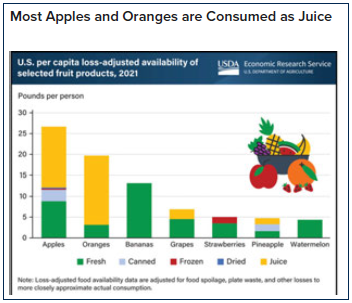

The US measures food availability rather than food consumption, since some of the fresh produce that is purchased is not consumed. USDA has a measure of loss-adjusted food availability that excludes food that is purchased and not eaten. It fnds apples and oranges were the most popular fruits in 2021 in terms of average pounds per person consumed, and that most apples and oranges were consumed as juice. Bananas and watermelons were almost all consumed fresh, as were most grapes and strawberries.

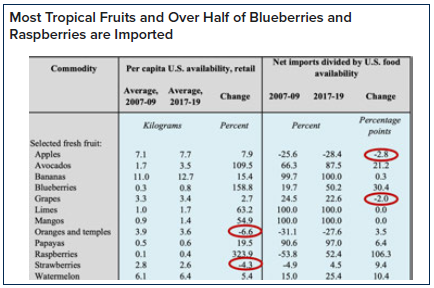

The per capita availability of many fresh fruits increased over the past decade, rising threefold for raspberries and more than doubling for blueberries and avocados. Most of the increased availability of fresh fruit was due to rising imports during the months when US production is low: 52 percent of US raspberries, 50 percent of blueberries, and 87 percent of avocados are imported. The US is a net exporter of fresh apples and oranges, explaining why the share of these commodities is negative.

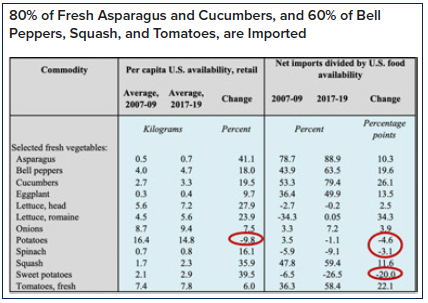

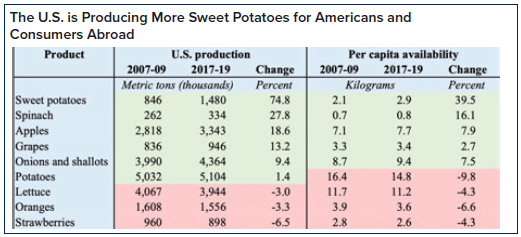

The availability of fresh vegetables increased more slowly. Potatoes and onions are the fresh vegetables with the largest per capita availability, and potato availability fell due to declining US consumption and rising exports. The fastest growth was in imports of asparagus and squash. The US is a net exporter of sweet potatoes, but almost 90 percent of US asparagus and 60 percent of US squash is imported.

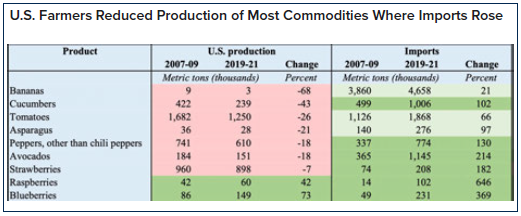

How have US farmers responded to rising fresh produce imports? US production of many fresh vegetables that compete with imports fell between 2007-09 and 2017-19, including cucumbers, peppers, and tomatoes. However, US production of blueberries and raspberries rose alongside rising imports, suggesting that increased consumption of these berries was satisfed by more US production and more imports.

US farmers increased their production of commodities that experienced rising demand in the US and abroad such as apples, grapes, sweet potatoes, and spinach.

Fresh Imports

The US imported 60 percent of its fresh fruit in 2021, or 50 percent if bananas are excluded. The US imports almost all of its bananas, mangos, papayas, and limes, 90 percent of its avocados, 80 percent of its raspberries, two-thirds of its blueberries, 55 percent if its grapes, and a third of its tangerines. About 20 percent of the lemons, oranges, and strawberries available to Americans are imported, but less than 10 percent of the apples, cherries, peaches, and nectarines are imported.

The share of US fresh fruit that is imported rose from 40 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2020 due to the especially sharp jumps in the import share of blueberries, from 40 percent to 70 percent, and strawberries, from seven to 21 percent.

The US imported 38 percent of its fresh vegetables in 2021, almost triple the 13 percent import share in 2000. The share of fresh tomatoes that were imported rose from 30 percent to 70 percent, while the import share of broccoli rose from eight to 32 percent.

Appendix

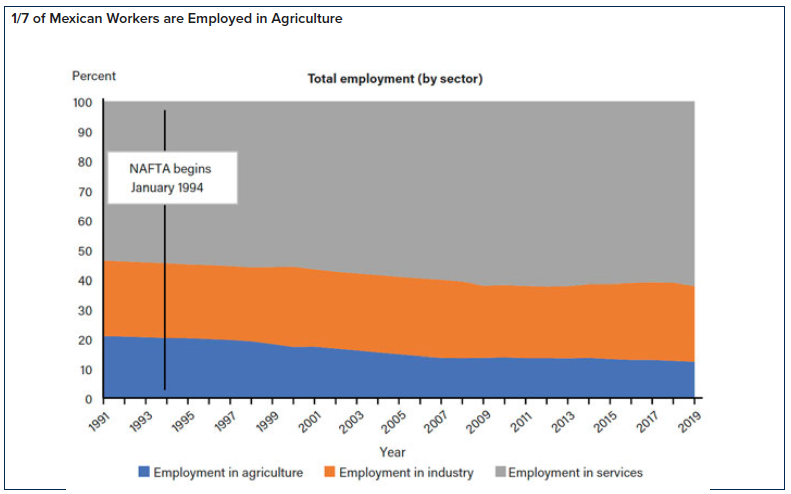

Employment in Mexican agriculture fell from over 20 percent of total employment to about 15 percent over the past three decades. Agricultural employment declined fastest between the peso crisis of the mid-1990s and the 2008 transition to freer trade in farm commodities. The share of employment in Mexican agriculture continues to decline, but at a slower pace.

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Water Security at the US-Mexico Border | Part 1: Background

China and the Chocolate Factory

Ongoing Debate: The Prohibition of GMO Corn in Mexico